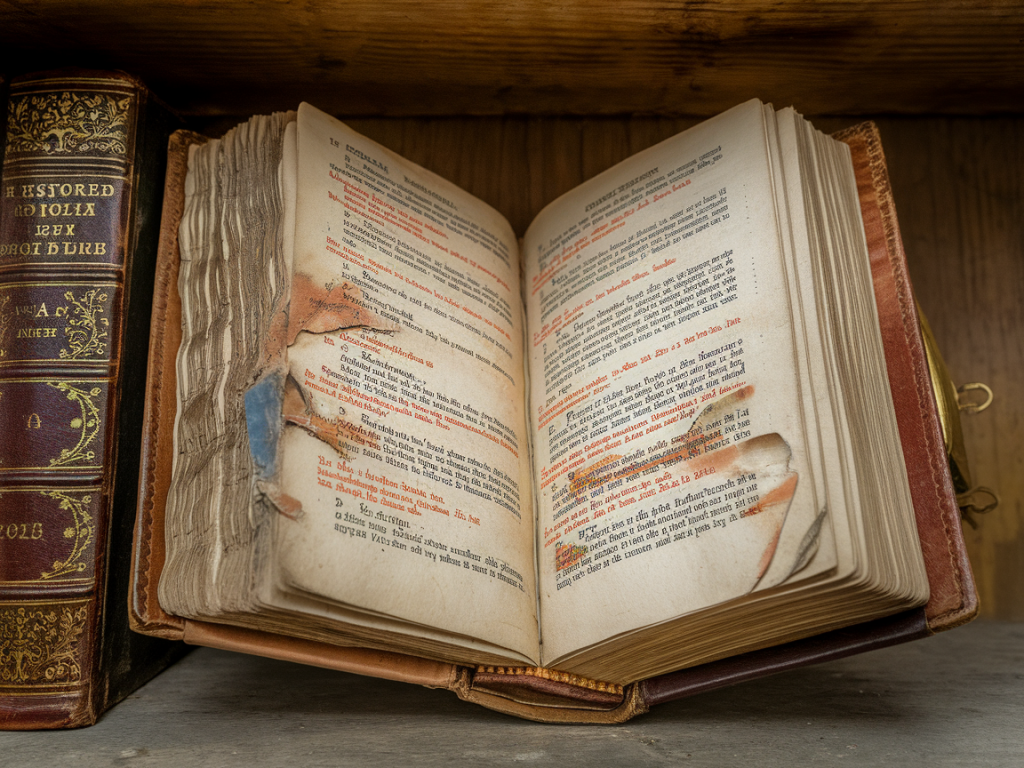

I remember the first time I opened a restored edition of a book I had already read in a cheaper paperback: the pages felt like someone had taken a curtain aside and shown me a room I thought I’d known. Restored and annotated editions do something like that. They don’t simply reprint words; they reframe, re-weigh and sometimes rewrite our relationship with a text. For books that have been neglected—out of print, misread, or climactically forgotten—this process can be quietly revolutionary.

What do we mean by “restored” and “annotated”?

“Restored” can mean different things in different contexts. Often it refers to an edition that reconstructs the text as the author intended: correcting typographical errors introduced by earlier printers, restoring excised passages, or choosing one authoritative manuscript over a mistaken transmission. “Annotated” usually means the text is accompanied by notes—glosses on obscure references, explanations of historical context, textual variants, or interpretative commentary.

Publishers I often turn to for these kinds of projects include NYRB Classics, Penguin Classics, Oxford World’s Classics and smaller, more curatorial houses like Pushkin Press and And Other Stories. Each has its own editorial philosophy: NYRB tends to foreground neglected writers with readable introductions; Oxford prioritises scholarly apparatus; Pushkin often blends literary discovery with attractive design. The differences matter because they influence how a neglected author will be reintroduced to readers.

How editorial choices change what a book “means”

When I read a restored edition, I’m reading two books at once: the novel or poem itself, and the editor’s version of its history. Editorial decisions—what to include in a foreword, which variant to adopt, how many footnotes to add—act like a lens. They emphasize certain lines of meaning while muting others.

Take textual variants. A single line changed by a compositor’s error can alter tone or implication. Restoring an original phrasing might clarify a character’s motivation or reveal an irony that previous editions blurred. Conversely, an editor’s choice to harmonise variants can create a smoother reading experience while eliminating the very ambiguities that made the original text interesting. Both choices are valid; the consequence is that readers will come away with a different sense of the book’s priorities.

Annotations do more than explain obscure words. They map the book into a world. A well-chosen annotation tells you who a minor historical figure was, the political context of an offhand remark, or a nod to another text that reshapes how you interpret a scene. For neglected books—especially those written outside dominant literary geographies or in another historical moment—these notes can be essential to appreciating why the book mattered then and why it might matter now.

Restored editions as acts of rescue

There is an ethical dimension to restoration. Neglected books often fall out of circulation because of economic neglect, political suppression, or simple accident. Editorial resurrection can be an act of cultural justice: bringing back texts by women writers, colonial-era authors, or marginalised voices who were never given a sustained critical apparatus.

But rescue is not neutral. I’m always attentive to who is doing the rescuing. A restoration led by a scholar with deep ties to the author’s language and cultural context will often be more sensitive than one driven solely by market opportunity. That’s why the growing work of translators and editors from within the communities whose literature they revive is so important: they can correct misreadings born of ignorance and highlight connections that outside readers might miss.

Examples that have changed how I read a text

- Jean Rhys (Virago Modern Classics and NYRB reissues): The annotations and new introductions surrounding her novels—especially the restored versions of her early work—recast Rhys from a marginal “tragic voice” to a modernist innovator whose fragmentary style emerges from exile and gendered vulnerability.

- Franz Kafka (new scholarly editions): Restored texts exposing variant drafts and editorial choices show how much of Kafka’s famous “ambiguity” is the result of his manuscripts’ complicated transmission, inviting us to read his unfinishedness as strategy rather than mere incompletion.

- Neglected colonial-era novels (restored translations by small presses): Annotations that clarify local political events, idiomatic language and social structures transform what had seemed like exoticism into precise accounts of power.

In each case the restored edition didn’t just make me notice small things; it rearranged the whole field of interpretation I thought I knew.

Paratext and the politics of framing

Paratext—the material that surrounds the main text: introductions, afterwords, cover notes, and footnotes—is where much of the interpretive work happens. Editors choose which biographical facts to emphasise, which critical debates to summarise, and which intertextual links to highlight. For neglected books, these choices can create a new critical identity.

For instance, an introduction that situates an author within a nationalist movement will prime readers to look for political allegory; an introduction that highlights the book’s formal innovations will push readers toward close stylistic analysis. Neither is “the” correct approach, but each routes the reader’s attention differently. That routing is enormously consequential when an author lacks a well-established critical tradition.

Practical advice for readers choosing an edition

- Decide what you want: Are you reading for pleasure, historical fidelity, or scholarly precision? A readable restored edition with a lively introduction (NYRB, Virago) suits general readers; Oxford World’s or a critical edition is better for research.

- Check the editor’s credentials: Look for translators and editors who write transparently about their methods and sources. Trustworthy introductions explain why certain choices were made.

- Compare editions if possible: When a book exists in both a popular reissue and a scholarly edition, skim the paratext to see which approach appeals to you. Different editions can complement each other.

- Consider the translation history: For works in translation, see whether a new translation claims fidelity to previously unavailable manuscripts or aims for contemporary readability. Both can be valuable, but they produce different experiences.

Why this matters now

We live in a moment when the literary canon is being actively interrogated. Restored and annotated editions are a crucial tool in that process: they provide the textual and contextual resources required to read more broadly and more carefully. For readers who cherish discovery—like those who visit Storyscoutes Co—these editions convert curiosity into knowledge. They let us approach neglected books not as curios but as living works with histories and claims on the present.

Finally, restoration is a reminder that books are not static objects. They travel through time, picked up, altered and sometimes abandoned. A restored edition says: this book still has something to tell us; here is how we might listen.