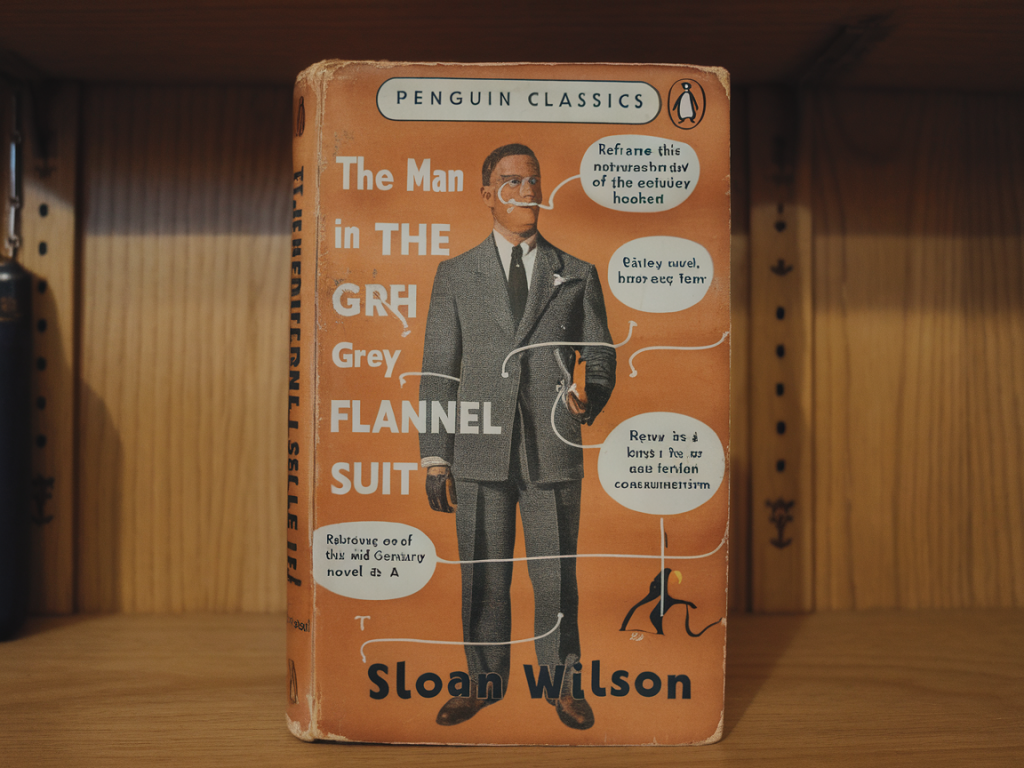

I first encountered a mid-century novel that had been quietly collecting dust on a secondhand shelf—its jacket browned at the edges, its spine a practiced bow from previous hands. The book was not unknown, merely neglected, sidestepped by later fashions in taste. I brought it home because of the strange particularity of its opening line, and then I turned to the Penguin Classics edition because, frankly, those little annotations felt like a co-conspirator: a guide that can nudge you toward seeing the book afresh rather than telling you what to think.

The promise of Penguin Classics annotations

Penguin Classics editions are useful not because they flatten a text into a single, authoritative interpretation, but because their annotations—glosses, introductions, explanatory notes—supply the scaffolding needed to notice what’s been overlooked. They situate the novel historically and linguistically, flag references that modern readers may miss, and often point toward other works or contexts that reframe the book’s concerns.

When approaching a neglected mid-century novel I use Penguin annotations to do three things: restore historical texture, reveal formal or stylistic experiments, and surface political or social conversations that have been muted over time. Those are broad aims, but they can be practised through a few concrete steps.

How I read with annotations: a practical approach

I recommend reading in two passes. The first pass is for getting lost; the second is for gathering the clues annotations provide.

During the second pass, I keep a notebook (or a digital document) with three columns: passage, annotation summary, question. For example:

| Passage | Annotation summary | Question |

|---|---|---|

| A domestic scene where the radio plays “a foreign ballad” | Notes identify the song’s possible origins and its contemporaneous popularity | Does the radio introduce an external world that destabilises domestic certainty? |

| A throwaway line about rationing | Notes explain post-war rationing policies | How does economic scarcity shape the characters’ moral choices? |

Reading the introduction as a tool, not a verdict

Penguin introductions can be tempting to read first because they summarise the book’s place in literary history. I usually skim the intro before the second pass to flag key themes, but I avoid treating it as a final verdict. An excellent introduction can open interpretive routes—context about the author’s life, publication history, initial reception—without closing off other readings.

Use the introduction to assemble a short research list: names, events, other works mentioned in the intro. Then follow one thread. For example, if the intro places the novel in a conversation with contemporary modernist experiments, find one or two of those experiments and see how the novel converses with them—does it mimic, parody, reject? That comparative glance often yields a new angle from which to argue for the book’s relevance.

Pay attention to what’s glossed—and what isn’t

Annotations reveal editorial decisions. When Penguin glosses a term or an event, it signals editorial judgement about what modern readers will miss. But equally revealing are the silences: what is unglossed, or given only a brief note? Those silences can point to assumed knowledge in mid-century readerships that we might recover to better understand the text.

I keep an eye out for three kinds of editorial choices:

Treat annotations as reading companions, not authority

Annotations are an invitation to dialogue. When a note suggests that a passage echoes another writer, I go and read that echo. Often the echo reconfigures the novel: perhaps it reveals a debt, a parody, or a deliberate divergence. But I resist letting the annotation become the interpretive endpoint. I ask: does the note illuminate the passage in a way that changes my emotional or intellectual response? Does it reveal a continuity I hadn’t suspected?

For example, a Penguin note might point out that a character’s gesture mirrors a symbol in a contemporary poem. Once you establish that connection, you can ask how the symbol functions differently in prose: is it ironic? Did the novelist domesticate the poem’s energy, or amplify it?

Use annotations to build reading routes

One of my favourite uses of Penguin notes is as a map for further reading. Annotations often mention other texts—novels, essays, journalism—that sat beside the neglected book in its own time. Following those references can transform a single neglected title into a micro-canon of related works, revealing cultural conversations that explain why the novel matters.

Make a “reading route” anchored on the novel: pick three references from the annotations and schedule short encounters with them. Aim for variety—a poem, a novel, and a newspaper piece, for instance. These detours can reveal how the novel participated in debates about gender, class, empire, or aesthetics that are still resonant.

When annotations fall short: doing your own archival work

Not every Penguin edition will have notes exhaustive enough for the questions you want to ask. If you find a gap—say, about a magazine the author contributed to, or a political movement mentioned in passing—use digital archives, JSTOR, or British Newspaper Archive to fill it. Even a few primary-source headlines or adverts can dramatically change how you read a passage about public opinion or social habit.

When I’ve dug into these sources, I often return to the book surprised at how vividly the world reappears: a line about an advert, suddenly anchored by an image; a reference to a speech, reframed by the actual rhetoric used at the time.

Annotate the annotated: make the Penguin edition your working copy

Finally, make the Penguin edition your own. I underline, bracket, and write marginal questions. I also add small sticky notes linking Penguin notes to other passages. Annotations are most useful when they become a conversation you can return to: a trail of breadcrumbs that leads not to the editorial conclusion but to your own reading discoveries.

Using Penguin Classics annotations this way—attentive, curious, interrogative—lets a neglected mid-century novel emerge less as a museum piece and more as a live conversation partner. The annotations don’t tell you what the book means; they help you see the ways it might mean different things to different readers across time.